This post is the translation of my blog bost from habr.com.

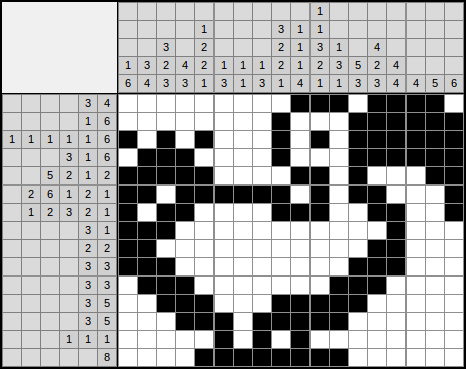

Japanese crosswords (aka nonograms) are picture logic puzzles. The solution of puzzles based on numbers which are placed to the left of the rows and on the top of the columns.

The size of the puzzle may be as big as 150x150. A player calculate the color of each cell with some special logical methods. The solution process can take a couple of minutes on puzzles for newcomers and dozens of hours on hard ones.

A good algorithm is capable to solve the task too much faster. In the post I described how to write a solution which works almost instantly, using most convenient algorithms (which lead to a solution in general), and their optimizations and features of C++ (which decrease the running time in dozens of times).

Game rules

At the start the canvas of the image is filled with white. For vanilla black-white crosswords it is needed to restore the positions of black cells.

In black-white crosswords the amount of numbers for each row (to the left of canvas) or for each column (on the top of canvas) defines how many groups of black cells (placed sequentially) are placed in the corresponding row or column, and the numbers themselves - the lengths of each group. The list of numbers $[3, 2, 5]$ means that in the corresponding line (row/column) there is three groups placed sequentially, of $3$, $2$ and $5$ black cells. Groups can be located as you wish, not breaking their relative order (since the numbers define their lengths, but the positions have to be guessed), but they should be divided by at least one white cell.

In colored crosswords each group has its color - any color except white, which is reserved for background. Neighboring groups of different colors can be placed back to back, but for the same color the division by at least one white cell is still necessary.

What is not a Japanese crossword

Every pixel image can be encoded to a puzzle. But it may be impossible to restore the image back - the resulting puzzle may have more than one solution, either have the single solution but can’t be solved in a logical way. Then the remaining cells are to be guessed using ~quantum computing~ shamanic technologies.

Such crosswords aren’t crosswords, but graphomania. It goes that a correct crossword - such a crossword in which using only a logical way it’s possible to reach the single solution.

A “logical way” is a possibility to restore each cell one by one, considering a row/column one by one either their intersection. If there isn’t such an opportunity, the amount of possible variants can be huge, way too bigger than people can calculate with a pen and paper.

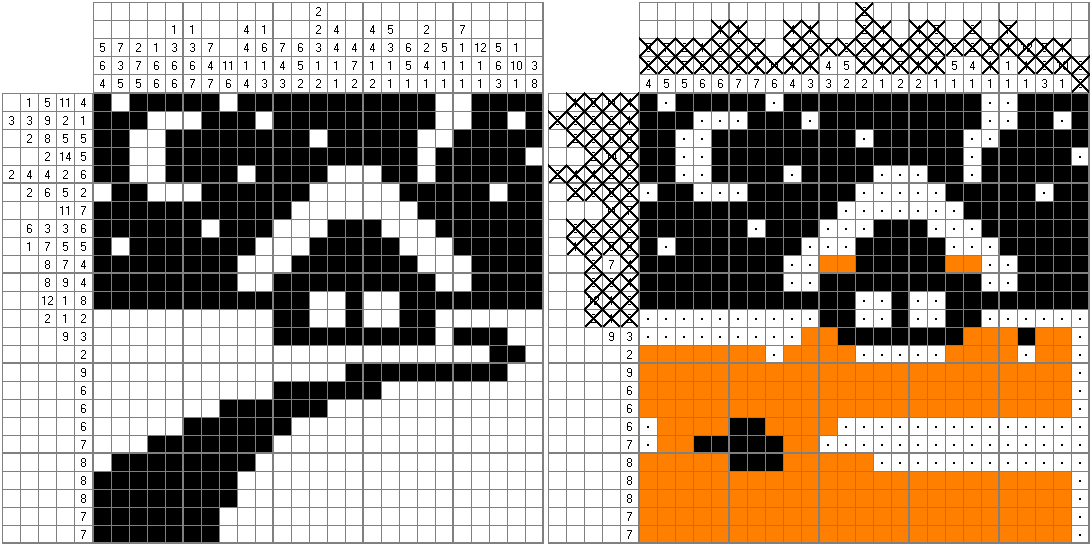

A wrong nonogram - the solution is single, but impossible to be found with a deterministic algorithm. “Unsolvable” cells filled with orange. The source of the image is Wikipedia.

A wrong nonogram - the solution is single, but impossible to be found with a deterministic algorithm. “Unsolvable” cells filled with orange. The source of the image is Wikipedia.

This limitation is explained in such a way - in the most common case the Japanese crossword is an NP-complete problem. However, it isn’t such a problem, if there is an algorithm which in every state uniquely calculates what cells are to be definitely guessed. All methods of solving crosswords, used by people (excepting ~Monte-Carlo~ trial and error method) are based on this.

The most orthodox crosswords have width and height what are divisible by 5, don’t have instantly-calculated lines (what don’t have groups at all or whose groups fill the entire line cell by cell definitely). These requirements are not mandatory.

The simplest wrong nonogram:

1

2

3

4

5

|1 1|

--+---+

1| |

1| |

--+---+

Encoded pixelart images often are not back-solvable, if they have a “chess order” to imitate gradient. You’ll get what it means by searching “pixelart gradient”. Pixelart gradients are similar to this fail 2x2 crossword.

Possible ways to solve

We have the dimensions of the puzzle, description of the colors and all the rows and columns. How to build the image from this:

Brute force

Iterate all possible states for each cell and check the satisfability. Complexity of such a solution for black-white crosswords is $O(N\times M\times {2}^{N\times M})$, for colored ones $O(N\times M\times {colors}^{N\times M})$. Like clown sort, this solution also can be named clownish. It’s good for 5x5 dimension.

Backtracking

Iterate all possible ways to place horizontal cell groups. Place a group of cells in a row, check that it didn’t break the description of columns cell groups. If it did - try to place the same group one cell further. If we placed successfully - go to the next group. If the group can’t be placed anyway - rool back two groups, check again, and so on, while we haven’t placed the last group correctly.

Separately for each line

This solution is way too better and is truly true. We can analyze each row and each column separately. For each line we try to reveal the maximum of information.

The algorithm reveals information for each cell in a line - it may turn out that it’s impossible to set a cell in a certain color, groups then won’t describe a right configuration anymore. We can’t reveal the whole row, but new information “helps” some columns reveal better, and when we analyze them, they will “help” rows back, and so on, during multiple iterations, while haven’t got a single possible color for each cell.

The truly true solution

One line, two colors

Effective guessing of one-line crosswords, in which some cells are already guessed, is a greatly tough task. It appeared in such contests as:

- Quarter-Final of ACM ICPC 2006 - you can try to solve the task yourself. Time limit - 1 second, limit of the groups number - 400, the length of the line - 400. It has a pretty strong level of difficulty compared to other tasks on the site.

- International Olympiad in Informatics 2016 - legend, send solution (warning, Russian-language server). Time limit - 2 seconds, limit of the groups number - 100, the length of the line - 200’000. These limitations are overkill, but a solution which passes the ACM task limits, gives 80/100 points in this task. The level of this contest is very hard, school students with cruel IQ from around the world train to solve bizarre tasks many years, then pass the competition to take part in this contest (only 4 people pass to the contest from each country each year), and solve 2 rounds for 5 hours each.

A monochrome one-liner can be solved using different ways, as with $O(N\times 2^N)$ (brute-forcing all states, check for correctness, detect the cells which have the same colors in all correct states), as well somehow less stupid.

The key idea is to use an analog of backtracking with avoiding redundant calculations. If we somehow placed some groups and currently we are in some cell, then we need to know, if it’s possible to place remaining groups starting from the current cell.

Pseudocode

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

def EpicWin(group, cell):

if cell >= last_cell: # The win condition

return group == group_size

win = False

# Check if we can place the group to the position

if group < group_size # There are some groups left

and CanInsertBlack(cell, len[group]) # Inserting black group

and CanInsertWhite(cell + len[group], 1) # Inserting white cell

and EpicWin(group + 1, cell + len[group] + 1): # Can fill further

win = True

can_place_black[cell .. (cell + len[group] - 1)] = True

can_place_white[cell + len[group]] = True;

# Check if we can place a white cell to the position

if CanInsertWhite(cell, 1)

and EpicWin(group, cell + 1):

win = True

can_place_white[cell] = True

return win

EpicWin(0, 0)

Such a method called dynamic programming. Note that the pseudocode is pretty simplified and we don’t even memoize the calculated values.

The functions CanInsertBlack/CanInsertWhite are needed to check if it’s possible to place a group of certain size and color in some position. All what they have to do is to check that in the specified segment there are no any “100% white” cell (for the first function) or “100% black” (for the second one). It means they can work with $O(1)$ complexity since it can be done via partial sums:

CanInsertBlack

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

white_counter = [ 0, 0, ..., 0 ] # An array of length n

def PrecalcWhite():

for i in range(0, (n-1)):

if is_anyway_white[i]: # 1, if the i-th cell is 100% white

white_counter[i]++

if i > 0:

white_counter[i] += white_counter[i - 1]

def CanInsertBlack(cell, len):

# Omitting checks of [cell, cell + len - 1] segment bounds correctness

ans = white_counter[cell + len - 1]

if cell > 0:

ans -= white_counter[cell - 1]

# ans contains the number of definitely white cells from \[cell\] to \[cell + len - 1\]

return ans == 0

We do the same witchcraft for lines like

1

can_place_black[cell .. (cell + len[group] - 1)] = True

Which imply changing a segment of an array. There we can increment (increase by 1) the element instead of = True. If we need to do a lot of summations on segments in an array, and we do not use the array somehow before different summations (it is said that the task “is solved offline”), then instead of the cycle:

1

2

3

# This is called many times

for i in range(L, R + 1):

array[i]++

We can do this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

# This is called many times

array[L]++

array[R + 1]--

# After all summations

for i in range(1, n):

array[i] += array[i - 1]

Thereby the algorithm works for $O(k\times n)$ complexity, where $k$ is the number of black cell groups, $n$ is the length of the line. And we pass to the Semi-Final of ACM ICPC or get a bronze medal of IOI. ACM solution (Java). IOI solution (C++).

One line, many colors

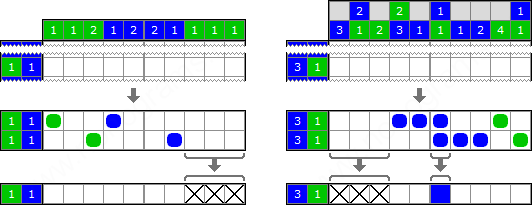

When looking at many-colored nonograms, for which we even still don’t know the solution, we learn a terrible truth - in fact, each row is affected by every column! It goes clear with an example:

Source - Methods of solving Japanese crosswords

Source - Methods of solving Japanese crosswords

Bicolored nonograms go well without this effect, they don’t need to look at orthogonal friends. The left example from the image has three empty cells at the right end, because the configuration breaks when we fill these cells with not white color.

But this connection can be resolved, if we give a number to each cell, where $i$-th bit means if it’s allowed to give the cell the $i$-th color. At the start each cell has the number $2^{colors} - 1$. The dynamic programming solution won’t change dramatically.

We can take notice on an effect: in the same left example, according to the rows, the most right cell can have either blue or white color. According to the columns, this cell has either green, or white color. According to common sense, this cell definitely has only white color. And we continue to calculate the answer.

If consider the $0$-th bit “white”, the first “blue”, the second “green”, then the row calculated for the last cell state $011$, the column $101$. It means that really the cell has state $011 \land 101=001$.

Pseudocode

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

source = [...] # States at the start of the algo

result = [0, 0, ..., 0] # States at the end

len = [...] # Lengths of cell groups

clrs = [...] # Colors of cell groups

def CanInsertColor(color, cell, len):

for i in range(cell, cell + len):

if (source[i] & (1 << color)) == 0: # Can't place this color in a certain cell

return False;

return True

def PlaceColor(color, cell, len):

for i in range(cell, cell + len):

result[i] |= (1 << color) # Add the color by the OR operation

def EpicWinExtended(group, cell):

if cell >= last_cell: # The win condition

return group == group_size

win = False

# Can insert the group in the position

if group < group_size # Have some groups left to be placed

and CanInsertColor(clrs[group], cell, len[group]) # Placing black group

and SequenceCheck() # If the next group has the same cell, check that

# we can place the white cell after the group

and EpicWin(group + 1, cell + len[group]): # Can fill further

win = True

PlaceColor(clrs[group], cell, len[group])

PlaceColor(0, cell + len[group], 1) # Place the white cell if needed

# Can insert the white cell in the position

# White color has bit index 0

if CanInsertWhite(0, cell, 1)

and EpicWinExtended(group, cell + 1):

win = True

PlaceColor(0, cell, 1)

return win

Many lines, many colors

Permanently update the state of all rows and columns, described in the last paragraph, while we have cells with more than one bit. In each iteration, after updating all rows and columns, update the states of all cells in them via mutual $\land$ (the AND operator).

First results

Let’s say that we didn’t write the code as woodpeckers, didn’t copy objects instead of passing by reference by mistake, didn’t mess up things in the code anywhere, weren’t inventing bicycles, used __builtin_popcount and __builtin_ctz for bit operations (gcc properties), and did things neat and clean.

Let’s look at the running time of the program, which reads the puzzle from a file and solves it completely. It’s worth to look at the working station properties, on which all the code has been written and tested:

Engine specs of my 1932 Harley Davidson Model B Classic Motorcycle

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

RAM - 4GB

CPU - AMD E1-2500, capacity 1400MHz

Cache L1 - 128KiB, 1GHz

Cache L2 - 1MiB, 1GHz

Cores - 2, threads - 2

Presented as "weakly productive SoC for compact laptops" mid-2013

Costs 28$

It’s clear that such a supercomputer was chosen, because optimizations have bigger effect on this, than on a flying devil-machines.

So, after launching our algorithm on the hardest puzzle (according to nonograms.org), we get not so good outcome - from 47 to 60 seconds (including reading from the file and solving). I need to notice that complexities of puzzles from nonograms.org are calculated well - the same crossword takes the top place of working time, as well as other most hard puzzles are in the top, in all versions of the program.

I added to the program an option to launch a benchmark on a folder. To get data I parsed 4683 colored nonograms (out of 10906) and 1406 black-white (out of 8293) from nonograms.org (this site is one of the biggest archives of nonograms) by a script and saved it in a format understandable to the program. We can consider these puzzles as random samples, therefore the benchmark shows adequate median and average values. Also the numbers of a couple of dozens of the most “hard” puzzles (and the biggest, and those that have the most colors) I wrote to the script by hands.

Optimization

Here I show optimization methods, which have been applied (1)while writing the entire algorithm, (2)to pressure the running time down from half a minute to fractions of a second, (3)possible methods which may be useful in the future.

While writing the algorithm

- Special functions for bit operations, in our case

__builtin_popcountto count bits set to 1 in the binary representation of a number, and__builtin_ctzto find the amount of trailing zeros of a number. Those functions may not exist in some compilers. For Windows you can use code like:

Windows popcount

1

2

3

4

#ifdef _MSC_VER

# include <intrin.h>

# define __builtin_popcount __popcnt

#endif

- Arrays organization - the smaller dimension stands at the beginning. For example, it’s better to use an array which looks like [2][3][500][1024], than [1024][500][3][2].

- The most important - adequacy of the code and avoiding to create redundant problems for CPU to calculate.

What decreases the execution time

- -O2 flag when compiling. (-O3 isn’t always good, but it’s not the theme of this article)

- To avoid “solving” already solved row/column again, store in a std::vector/array flags for each line, mark a line when solved, and don’t allow to go further, when iterating the lines and meeting already solved one.

- Specificity of a multi-repetitive solution that used dynamic programming several times, assumes that the array which marks already “calculated” pieces of the tasks, is needed to be cleared every new iteration. In our case it is a two-dimensional array/vector, where the first dimension is the amount of the groups, the second one is the current cell (look the

EpicWinpseudocode above for details, where there the array doesn’t exist, but the idea is clear). Instead of zeroing out we can do this way - let we have a variable named “timer”, and the array consists of numbers which show the last “time” when this piece was recalculated earlier. When starting a new subtask, icrement the “timer”. Instead of checking boolean flags it’s needed to check the equality of the “timer” and elements of the array. This is especially effective when the algorithm doesn’t look at absolutely all states (let’s say, 50%-90% or even 5% in some cases), and that means that zeroing out the array “did we calculated this” takes a great amount of time). - Change simple same-type operations (loops with assignments, etc.) to their analogs in STL or other more adequate things. Sometimes it works faster that an invented wheel.

std::vector<bool>in C++ saves all boolean values as bits in an integer type to save memory. It works slightly slower on access, comparing with a regular value by an address. If a program accesses extremely often, changing bool to an integer type can affect program’s perfomance in a good direction.- Other weak places can be found via profilers. I use Valgrind, its dumps are easy to explore in kCachegrind. Profilers are embedded to many IDEs.

These changes were enough to get this benchmark outcome:

Colored nonograms

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

izaron@izaron:~/nonograms/build$ ./nonograms_solver -x ../../nonogram/source2/ -e

[2018-08-04 22:57:40.432] [Nonograms] [info] Starting a benchmark...

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] Average time: 0.00497556, Median time: 0.00302781, Max time: 0.215925

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] Top 10 heaviest nonograms:

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.215925 seconds, file 9596

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.164579 seconds, file 4462

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.105828 seconds, file 15831

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.08827 seconds, file 18353

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.0874717 seconds, file 10590

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.0831248 seconds, file 4649

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.0782811 seconds, file 11922

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.0734325 seconds, file 4655

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.071352 seconds, file 10828

[2018-08-04 22:58:03.820] [Nonograms] [info] 0.0708263 seconds, file 11824

Black-white nonograms

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

izaron@izaron:~/nonograms/build$ ./nonograms_solver -x ../../nonogram/source/ -e -b

[2018-08-04 22:59:56.308] [Nonograms] [info] Starting a benchmark...

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] Average time: 0.0095679, Median time: 0.00239274, Max time: 0.607341

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] Top 10 heaviest nonograms:

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.607341 seconds, file 5126

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.458932 seconds, file 19510

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.452245 seconds, file 5114

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.19975 seconds, file 18627

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.163028 seconds, file 5876

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.161675 seconds, file 17403

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.153693 seconds, file 12771

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.146731 seconds, file 5178

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.142732 seconds, file 18244

[2018-08-04 23:00:09.781] [Nonograms] [info] 0.136131 seconds, file 19385

Noticeable that black-white crosswords are “harder” than colored ones in average. It confirms observations of crossword solvers who also believe that “colored” puzzles are solved easily in average.

In this way, without radical changes (like rewritting all the code on C or pieces of assembler code with a fastcall convention and omitting a frame pointer) it’s possible to get high perfomance, notice, on a strongly weak computer. Optimizations may have the Pareto principle - a small optimization may drastically affect the program, because this piece of code is critical and is called very often.

Further optimizations

Following methods can drastically improve the perfomance of a program. Some of them require special conditions and don’t work in all cases.

- Rewritting the code to C-style and other 1972 stuff. Change ifstream to a C analog, vectors to arrays, learn all compiler options and struggle for each CPU’s tick.

- Paralleling. For example, there is a piece in the code, where the rows and the columns are updated one by one:

bool Puzzle::UpdateState(…)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

...

if (!UpdateGroupsState(solver, dead_rows, row_groups, row_masks)) {

return false;

}

if (!UpdateGroupsState(solver, dead_cols, col_groups, col_masks)) {

return false;

}

return true;

These functions are independent one of each other and don’t have mutual memory to access instead of solver variable (of type OneLineSolver), so it’s possible to create two objects of OneLineSolver and start two threads in the function. The effect is - in colored crosswords “the hardest” is solved two times faster, in black-white the same is solved 1/3 faster, but the average time increased due to relatively expensiveness of creating threads.

But really I’d not suggest to do it right how is described here - firstly, creating threads is a expensive operation, it’s not worth it to create threads for microseconds tasks, and secondly, using some combination of command line arguments in my program, these threads potentially can access some outer memory simultaneously, for example, when creating solution images - this should be taken into account and secured.

If the tasks was serious and I had many input data and multi-core machines, I would go further - it’s possible to create some permanent threads, and each will have its own OneLineSolver object, and there would be a thread-safe structure to rule distribution of work, which gives a reference to current row/column to solver. Threads after solving their tasks ask the structure for the next piece of work. Some puzzles may start to being solved before the last puzzle is solved to the end - while some threads upsolving the puzzle, the rest go forward. Paralleling could be done via graphics processor unit with CUDA - there is a plenty of variants.

- Using classical data structures. Notice - when I showed the pseudocode of the solution of colored nonograms, the functions

CanInsertColorandPlaceColordon’t work for $O(1)$, unlike black-white ones. In the program it looks as:

CanPlaceColor and SetPlaceColor

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

bool OneLineSolver::CanPlaceColor(const vector<int>& cells, int color,

int lbound, int rbound) {

// Went out of the border

if (rbound >= cells.size()) {

return false;

}

// We can paint a block of cells with a certain color if and only if it is

// possible for all cells to have this color (that means, if every cell

// from the block has color-th bit set to 1)

int mask = 1 << color;

for (int i = lbound; i <= rbound; ++i) {

if (!(cells[i] & mask)) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

void OneLineSolver::SetPlaceColor(int color, int lbound, int rbound) {

// Every cell from the block now can have this color

for (int i = lbound; i <= rbound; ++i) {

result_cells_[i] |= (1 << color);

}

}

It work with linear complexity, for $O(N)$ (I’ll explain this later)

Let’s look how to obtain better complexity. Take CanPlaceColor. This function checks that for each number in the segment $[lbound, rbound]$ the $color$-th bit is set to 1. As well we can take the $\land$ of all numbers of the segment and check the $color$-th bit. Using the fact that the $\land$ operation is commutative like sum, min/max, multiplication or the $\oplus$ (xor) operation, to calculate the $\land$ of a segment quickly we can use any data structure which is good with commutative operations on segments. It includes:

- SQRT-Decomposition. Precalc for $O(\sqrt{N})$, query for $O(\sqrt{N})$.

- Segment Tree. Precalc for $O(N\log{N})$, query for $O(\log{N})$.

- Sparse Table. Precalc for $O(N\log{N})$, query for $O(1)$.

It’s a pity that especially strong witchcrafts like the Farach-Colton and Bender algorithm (precalc for $O(N)$, query for $O(1)$) are useless for the task, because while learning the papers it turns out that the algorithm is created only for such operations $\varphi$, that $\varphi(\alpha, \beta) \in \lbrace \alpha, \beta \rbrace$, it means, the result of an operator should be one of the arguments.

Now take SetPlaceColor. There it’s needed to do an operation on segments of an array. It could be done via SQRT-Decomposition or Segment Tree with lazy propagation (aka “with pushes”). And for both of the functions simultaneously it’s possible to use cool data structure - Implicit Treap with updating and querying for logarithm.

Also we can expand the algorithm for black-white puzzles - use partial sums for all colors.

So, we have a serious question - why don’t we use all these gems of computer science, but do all the things for linear time? I have some answers:

- Smaller complexity of calculating doesn’t mean smaller amount of working time. An algorithm for $\log$ may require some precalculations, memory allocating, other shaking of resources - this algorithm can have pretty big constant (by “constant” I mean not a “magic number” in some neural networks, I mean the affect of the working time). Obviously if we have $N=10^{5}$, then an algo for $O(N^2)$ will work say 10 seconds, and an algo of $O(N\log{N})$ for say 0.150 seconds, but things can change on small enough $N$-s. It becomes more complicated when complexities are similar and it’s complex for one complexity to beat another complexity (it’s a complex joke): $O(N\sqrt{N})$ versus $O(N\log^2{N})$. In our task $N$ (the length of the row/col) is very small - 15-30 in average.

- There can be too small queries, enough to make precalculations for cool algorithms useless and resources-consuming for nought.

That is, the explanation is simple - both of these items are in effect, and inserting these wonderworks of programmer thought instead of the stupid algo either optimize the program very slightly, or increase the time of work due to specificity of calcuations - very small $N$ and not so big amount of queries. The fact about quieries is approved by the profiler, which thinks that these functions take ~25% and ~11% of the entire time respectively, that is, pretty small for a potential program’s weak spot. Even if we have a big complexity estimate, it’s good to understand that in such types of tasks this is “complexity from above” (extreme input data which may not exist at all), but the real working time on a random puzzle is too way smaller.

But don’t forget about the data structures at all - they can become useful in other cases, so I included them in the optimization list. Let’s look forward.

- Algorithm tuning. It may turn out that in average the algorithm works noticeably better if we change something unobvious. In our case it would be this approach: it’s logical to predict that if we updated the state of a row successfully, then its updated cells are likely to “trigger” corresponding columns? It means, it may be better to update these columns as fast as possible, right after this row! So we have a queue of subtasks. I didn’t try this algorithm, maybe it’s really faster on our dataset.

- Sudden changes in technical requirements (now we have crosswords with 1337 colors or with dimension 1000x1000) also require optimizations. To handle big amount of colors it’s okay to use fast std::bitset, big dimensions are good with data structures described above, and so on.

That’s all, here some cool optimizations. “Shoving” an algorithm depending on technical requirements is fun and informative. You can learn some cool things like embedded implicit treap in C++ (it is rope from the <ext/rope> header, but own writings work faster very often than the “default” one), special embedded types of trees and hidden hashtable which works faster 3-6 times on inserting/removing and 4-10 times on writing/reading, than unordered_map. Not even saying about different non-standart things, for example, from Boost.

ROFL Omitting Format Language

Inspired by geniuses of bygone days and their thought products, in particular, by brand new archiving algorithms and operating system with not boring wallpapers (if you don’t get it: these are well-known memes in the Russian IT community), I came up with brand new format of image files based on Japanese Puzzles and the Dunning–Kruger effect.

ROFL is a recursive acronym like “GNU’s Not Unix”. Well, the point of the format is to encode the image in the form of the Japanese puzzle, and an image editor should solve the puzzle to read the image. Hence the word “Omitting” in the name - the format omits the real image (btw, it can be useful in cryptography: you can pass Japanese crosswords with encoded passwords - all hackers will be going to be mad). Better if the format would look like Matroska - at the start of the file we have 4 bytes [52][4F][46][4C], then the image dimensions and the count of colors in the next 3 bytes, then all the colors, each by 3 bytes, and then the description of each group - its length, amount of cells and colors.

The format is free, MIT license, financial fees are volunteer - you can buy me a cup of coffee as for the author.

Sources

Program sources are hosted on GitHub. The program has many argument flags, generation of crosswords from images, generation of images from crosswords (by the way, almost all images in the post was generated by the code). I used additional libraries Magick++ and args.

I added a folder with some image examples, taken from the Internet (they are not part of the project). Parsed thousands of images from nonograms.org I didn’t host anywhere (and will not do) to protect the author rights.

I want to express special grattitude to the author of nonograms.org Chugunnyy K. A. (also known as KyberPrizrak) for the creation a wonderful, one of the biggest and the best site about nonograms, and for permission to use materials from the site for the post! All examples from the post I took from nonograms.org, here the list of source links.